Section 1: 99.9% Safe Maneuvers

Let’s face it, nuclear weapons are the elephant in the room that no one likes to talk about. So let’s approach the issue from the less threatening perspective of the awesome picture below.

The glider looks like it’s suspended above the runway, but in reality it’s screaming toward the photographer at 150 mph in a maneuver known as a high speed low pass. The pilot starts about 2000 feet high and a mile from the runway. He then dives to convert altitude into speed and skims the runway. Next, he does a steep climb to reconvert some of that speed into altitude so he can turn and land.

Given that the glider has no engine, you might wonder how the pilot can be sure he’ll gain enough altitude in the climb to safely turn and land. The laws of physics tell us exactly how altitude is traded for speed and vice versa. While there is a loss due to the air resistance of the glider, that is a known quantity which the pilot takes it into account by starting from a higher altitude than needed for the landing phase.

But it’s important to read the fine print in that guarantee provided by the laws of physics. It only applies if the air is stationary. If there’s a slight wind the difference is negligible, but if the air movement is unusually strong all bets are off – which is what happened to a friend of mine who had safely executed the maneuver many times before. But this time he hit an unusually strong, continuous downdraft. The laws of physics still applied, but the model of stationary air was no longer applicable and he had no way of knowing his predicament until he approached the runway with much less speed than needed for a safe landing. He managed to land without damage to himself or his glider, but was so shaken that he no longer does that maneuver.

While most experienced glider pilots sometimes do low passes (and some race finishes require them), I’ve opted not to because I regard them as a 99.9% safe maneuver – which is not as safe as it sounds. A 99.9% safe maneuver is one you can execute safely 999 times out of a thousand, but one time in a thousand it can kill you.

Even though they are clearly equivalent, one chance in a thousand of dying sounds a lot riskier than 99.9% safe. The perspective gets worse when it’s recognized that the fatality rate is one in a thousand per execution of the maneuver. If a pilot does a 99.9% safe maneuver 100 times, he stands roughly a 10% chance of being killed. Worse, the fear that he feels the first few times dissipates as he gains confidence in his skill. But that confidence is really complacency, which pilots know is our worst enemy.

A similar situation exists with nuclear weapons. Many people point to the absence of global war since the dawn of the nuclear era as proof that these weapons ensure peace. The MX missile was even christened the Peacekeeper. Just as the laws of physics are used to ensure that a pilot executing a low pass will gain enough altitude to make a safe landing, a law of nuclear deterrence is invoked to quiet any concern over possibly killing billions of innocent people: Since World War III would mean the end of civilization, no one would dare start it. Each side is deterred from attacking the other by the prospect of certain destruction. That’s why our current strategy is called nuclear deterrence or mutually assured destruction (MAD).

But again, it’s important to read the fine print. It is true that no one in his right mind would start a nuclear war, but when people are highly stressed they often behave irrationally and even seemingly rational decisions can lead to places that no one wants to visit. Neither Kennedy nor Khrushchev wanted to teeter on the edge of the nuclear abyss during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, but that is exactly what they did. Less well known nuclear near misses occurred during the Berlin crisis of 1961, the Yom Kippur War of 1973 and NATO’s Able Archer exercise of 1983. In each of those episodes, the law of unintended consequences combined with the danger of irrational decision making under stress created an extremely hazardous situation.

Because the last date for a nuclear near miss listed above was 1983, it might be hoped that the end of the Cold War removed the nuclear sword hanging over humanity’s head. Aside from the fact that other potential crises such as Taiwan were unaffected, a closer look shows that the Cold War, rather than ending, merely went into hibernation. In the West, the reawakening of this specter is usually attributed to resurgent Russian nationalism, but as in most disagreements the other side sees things very differently.

The Russian perspective sees the United States behaving irresponsibly in recognizing Kosovo, in putting missiles (albeit defensive ones) in Eastern Europe, and in expanding NATO right up to the Russian border. For our current purposes, the last of these concerns is the most relevant because it involves reading the fine print – in this case, Article 5 of the NATO charter which states that an attack on any NATO member shall be regarded as an attack on them all. It is partly for that reason that a number of former Soviet republics and client states have been brought into NATO and that President Bush is pressing for Georgia and the Ukraine to be admitted. Once these nations are in NATO, the thinking goes, Russia would not dare try to subjugate them again since that would invite nuclear devastation by the United States, which would be treaty bound to come to the victim’s aid.

But, just as the laws of physics depended on a model that was not always applicable during a glider’s low pass, the law of deterrence which seems to guarantee peace and stability is model-dependent. In the simplified model, an attack by Russia would be unprovoked. But what if Russia should feel provoked into an attack and a different perspective caused the West to see the attack as unprovoked?

Just such a situation sparked the First World War. The assassination of Austria’s Archduke Ferdinand by a Serbian nationalist led Austria to demand that it be allowed to enter Serbian territory to deal with terrorist organizations. This demand was not unreasonable since interrogation of the captured assassins had shown complicity by the Serbian military and it was later determined that the head of Serbian military intelligence was a leader of the secret Black Hand terrorist society. Serbia saw things differently and rejected the demand. War between Austria and Serbia resulted, and alliance obligations similar to NATO’s Article 5 then produced a global conflict.

When this article was first written in May 2008, little noticed coverage of a dispute between Russia and Georgia [Champion 2008] reported that “Both sides warned they were coming close to war.” As it is being revised, in August 2008, the conflict has escalated to front page news of a low-intensity, undeclared war. If President Bush is successful in his efforts to bring Georgia into NATO, and especially if the conflict should escalate further, we would face the unpleasant choice of reneging on our treaty obligations or threatening actions which risk the destruction of civilization. A similar risk exists between Russia and Estonia, which is already a NATO member.

Returning temporarily to soaring, although I will not do low passes, I do not judge my fellow glider pilots who choose to do them. Rather, I encourage them to be keenly aware of the risk. The pilot in the photo has over 16,000 flight hours, has been doing low passes at air shows for over 30 years, will not do them in turbulent conditions, ensures that he has radio contact with a trusted spotter on the ground who is watching for traffic, and usually does them downwind so that he only has to do a “tear drop” turn to land. The fact that such an experienced pilot exercises that much caution says something about the risk of the maneuver. The danger isn’t so much in doing low passes as in becoming complacent if we’ve done them 100 times without incident.

In the same way, I am not arguing against admitting Georgia to NATO or suggesting that Estonia should be kicked out. Rather, I encourage us to be keenly aware of the risk. If we do that, there is a much greater chance that we will find ways to lessen the true sources of the risk, including patching the rapidly fraying fabric of Russian-American relations. The danger isn’t so much in admitting former Soviet republics into NATO as in becoming complacent with our ability to militarily deter Russia from taking actions we do not favor.

Section 2: Substates

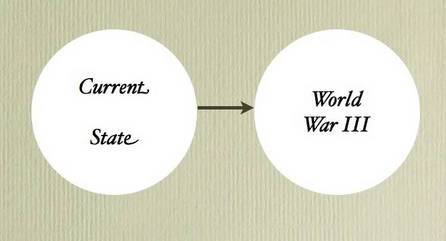

Part of society’s difficulty in envisioning the threat of nuclear war can be understood by considering Figure 2 below:

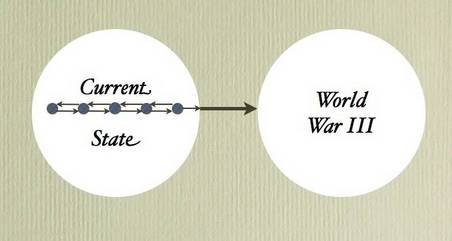

The circle on the left represents the current state of the world, while the one on the right represents the world after a full-scale nuclear war. Because World War III is a state of no return, there is no path back to our current state. Even though an arrow is shown to indicate the possibility of a transition from our current state to one of global war, that path seems impossible to most people. How could we possibly transit from the current, relatively peaceful state of the world to World War III? The answer lies in recognizing that what is depicted as a single, current state of the world is much more complex. Because that single state encompasses all conditions short of World War III, as depicted below, it is really composed of a number of substates – world situations short of World War III, with varying degrees of risk:

Society is partly correct in thinking that a transition from our current state to full-scale war is impossible because, most of the time, we occupy one of the substates far removed from World War III and which has little or no chance of transiting to that state of no return. But it is possible to move from our current substate to one slightly closer to the brink, and then to another closer yet. As described below, just such a sequence of steps led to the Cuban Missile Crisis and could lead to a modern day crisis of similar magnitude involving Estonia, Georgia, or other some other hot spot where we are ignoring the warning signs.

The Cuban Missile Crisis surprised President Kennedy, his advisors, and most Americans because we viewed events from an American perspective and thereby missed warning signs visible from the Russian perspective. Fortunately, that view has been recorded by Fyodr Burlatsky, one of Khrushchev’s speechwriters and close advisors, as well as a man who was in the forefront of the Soviet reform movement. While all perspectives are limited, Burlatsky’s deserves our attention as a valuable window into a world we need to better understand:

In my view the Berlin crisis [of 1961] was an overture to the Cuban Missile Crisis and in a way prompted Khrushchev to deploy Soviet missiles in Cuba. … In his eyes [America insisting on getting its way on certain issues] was not only an example of Americans’ traditional strongarm policy, but also an underestimation of Soviet might. … Khrushchev was infuriated by the Americans’ … continuing to behave as if the Soviet Union was still trailing far behind. … They failed to realize that the Soviet Union had accumulated huge stocks [of nuclear weapons] for a devastating retaliatory strike and that the whole concept of American superiority had largely lost its meaning. … Khrushchev thought that some powerful demonstration of Soviet might was needed. … Berlin was the first trial of strength, but it failed to produce the desired result, [showing America that the Soviet Union was its equal] . [Burlatsky 1991, page 164]

[In 1959 Fidel Castro came to power and the U.S.] was hostile towards the Cuban revolutionaries’ victory from the very start. … At that time Castro was neither a Communist nor a Marxist. It was the Americans themselves who pushed him in the direction of the Soviet Union. He needed economic and political support and help with weapons, and he found all three in Moscow. [Burlatsky 1991, page 169]

In April 1961 the Americans supported a raid by Cuban emigrees … The Bay of Pigs defeat strained anti-Cuban feelings in America to the limit. Calls were made in Congress and in the press for a direct invasion of Cuba. … In August 1962 an agreement was signed [with Moscow] on arms deliveries to Cuba. Cuba was preparing for self-defense in the event of a new invasion. [Burlatsky 1991, page 170]

The idea of deploying the missiles came from Khrushchev himself. … Khrushchev and [Soviet Defense Minister] R. Malinovsky … were strolling along the Black Sea coast. Malinovsky pointed out to sea and said that on the other shore in Turkey there was an American nuclear missile base [which had been recently deployed]. In a matter of six or seven minutes missiles launched from that base could devastate major centres in the Ukraine and southern Russia. … Khrushchev asked Malinovsky why the Soviet Union should not have the right to do the same as America. Why, for example, should it not deploy missiles in Cuba? [Burlatsky 1991, page 171]

In spite of the similarity between the Cuban and Turkish missiles, Khrushchev realized that America would find this deployment unacceptable and therefore did so secretly, disguising the missiles and expecting to confront the U.S. with a fait accompli. Once the missiles were operational, America could not attack them or Cuba without inviting a horrific nuclear retaliation. (The Turkish missiles had a similar purpose from an American point of view.) However, Khrushchev did not adequately envision what might happen if, as did occur, he was caught in the act.

With respect to the Cuban Missile Crisis, the substates of Figure 3 which brought us to the brink of nuclear war can now be identified as:

- conflict between America and Castro’s Cuba;

- Russia demanding to be treated as a military equal and being denied this status;

- the Berlin Crisis;

- the Bay of Pigs invasion;

- the American deployment of IRBM’s in Turkey; and

- Khrushchev’s deployment of IRBM’s in Cuba

The actors involved in each step did not perceive their behavior as overly risky. But compounded and viewed from their opponent’s perspective, those steps brought the world to the brink of disaster. During the crisis, there were additional, fortunately unvisited substates that would have made World War III even more likely. As just one example, the strong pressure noted by Burlatsky to correct the Bay of Pigs fiasco and remove Castro with a powerful American invasion force intensified after the Cuban missiles were discovered. But those arguing in favor of invasion were ignorant of the fact – not learned in the West until many years later – that the Russians had battlefield nuclear weapons on Cuba and came close to authorizing their commander on the island to use them without further approval from Moscow in the event of an American invasion.

Section 3: Risk Analysis

I have been concerned with averting nuclear war for over twenty-five years, but an extraordinary new approach only occurred to me last year: using quantitative risk analysis to estimate the probability of nuclear deterrence failing. This approach is a bit like Superman disguised as mild-mannered Clark Kent but, before I can explain why it is extraordinary, we need to explore what it is and overcome a key mental block that helps explain why no one previously had thought of applying this valuable technique.

To understand this mental block, imagine someone gives us a trick coin, weighted so heads and tails are not equally likely, and we need to estimate the chance of its showing heads when tossed. What do we learn if we toss the coin fifty times and it comes up tails every time? Statistical analysis says we can be moderately confident (95% to be precise) that the chance of heads is somewhere between zero and 6% per toss, but that leaves way too much uncertainty.

Thinking of the fifty years that deterrence has worked without a failure as the fifty tosses of the the coin, we are moderately confident that the chance of nuclear war is somewhere between zero and 6% per year. But there is a big difference between one chance in a billion per year and 6% per year, both of which are in that range. At one chance in a billion per year, a few more years of business as usual would be an acceptable risk. But 6% corresponds to roughly one in 16 odds, in which case our current nuclear strategy would be the equivalent of playing nuclear roulette – a global version of Russian roulette – once each year with a 16 chambered revolver.

Just as the overly simplified two-state model of Figure 2 hides the danger of a nuclear war, the coin analogy hides the possibility of teasing much more information from the historical record – the two-sided coin corresponding to Figure 2’s two states. Breaking down one large state of Figure 2 into Figure 3’s smaller substates illuminated the danger hidden in the two state model. In the same way, risk analysis breaks down a catastrophic failure of nuclear deterrence into a sequence of smaller failures, many of which have occurred and whose probabilities can therefore be estimated.

Modern risk analysis techniques first came to prominence with concerns about the safety of nuclear reactors, and in particular with the 1975 Rasmussen Report produced for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. In Risk-Benefit Analysis, Wilson and Crouch note “[The Rasmussen report] used event tree analysis … This new approach originally had detractors, and indeed the failure … to use it may have contributed to the occurrence of the Three Mile Island Accident. If the event tree procedure … had been applied to [the reactor design used at Three Mile Island] … probably the Three Mile Island incident could have been averted.” [Wilson and Crouch 2001, pp. 172-173]

An event tree starts with an initiating event that stresses the system. For a nuclear reactor, an initiating event could be the failure of a cooling pump. Unlike the catastrophic failure which has never occurred (assuming we are analyzing a design different from Chernobyl’s), such initiating events occur frequently enough that their rate of occurrence can be estimated directly. The event tree then has several branches at which the initiating event can be contained with less than catastrophic consequences, for example by activating a backup cooling system. But if a failure occurs at every one of the branches (e.g., all backup cooling systems fail), then the reactor fails catastrophically. Probabilities are estimated for each branch in the event tree and the probability of a catastrophic failure is obtained as the product of the individual failure probabilities.

Applying risk analysis to the catastrophic failure of nuclear deterrence, a perceived threat by either side is an example of an initiating event. If either side exercises adequate caution in its responses, such an initiating event can be contained and the crisis dies out. But the event tree consisting of move and counter-move can fail catastrophically and result in World War III if neither side is willing to back down from the nuclear abyss, as almost happened with the 1962 Cuban crisis. Each branch or partial failure corresponds to moving one or more substates toward disaster in Figure 3.

Because nuclear deterrence has never completely failed, the probability assigned to the last branch in the event tree (the final transition in Figure 3) will involve subjectivity and have more uncertainty. Confidence in the final result can be increased by incorporating a number of expert opinions and using a range instead of a single number for that probability, as well as providing justifications for the different opinions.

The Cuban Missile Crisis provides a good example of how to estimate that final probability. President Kennedy estimated the odds of the crisis going nuclear as “somewhere between one-in-three and even.” His Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, wrote that he didn’t expect to live out the week, supporting an estimate similar to Kennedy’s. At the other extreme McGeorge Bundy, who was one of Kennedy’s advisors during the crisis, estimated those odds at 1%.

In a recently published preliminary risk analysis of nuclear deterrence [Hellman 2008] I used a range of 10% to 50%. I discounted Bundy’s 1% estimate because invading Cuba was a frequently considered option, yet no Americans were aware of the Russian battlefield nuclear weapons which would have been used with high probability in that event. As an example of faulty reasoning due to this lack of information, Douglas Dillon, another member of Kennedy’s advisory group, wrote, “military operations looked like they were becoming increasingly necessary. … The pressure was getting too great. … Personally, I disliked the idea of an invasion [of Cuba] … Nevertheless, the stakes were so high that we thought we might just have to go ahead. Not all of us had detailed information about what would have followed, but we didn’t think there was any real risk of a nuclear exchange.” [Blight & Welch 1989, page 72]

The sequence of steps previously listed as leading up to the Cuban Missile Crisis is an example of an event tree that nearly led to a catastrophic failure, and reexamining those steps in the light of similar current events will show that, contrary to public opinion which sees the threat of nuclear war as a ghost of the past, the danger is lurking in the shadows, waiting until once again it can surprise us by suddenly leaping into clear view as it did in 1962:

Step #1: conflict between America and Castro’s Cuba:

The current conflicts between Russia and a number of former Soviet client states are similar. For example, as noted earlier, President Bush is pushing for Georgia to become a NATO member even though Russia and Georgia just fought an undeclared war over still unresolved issues

Step #2: Russia demanding to be treated as a military equal and being denied this status:

The same is true today. Even though Russia has 15,000 nuclear weapons, America sees itself as the sole remaining superpower, leading even Mikhail Gorbachev to say recently, “there is just one thing that Russia will not accept … the position of a kid brother, the position of a person who does what someone tells it to do.” [Tatsis 2008] Repeated American statements that we defeated Russia in the Cold War add fuel to that fire since the Russians feel they were equal participants in ending that conflict.

Steps #3 and #4: The Berlin Crisis and the Bay of Pigs invasion:

Several potential crises are brewing (e.g., Chechnya, Georgia, Estonia, and Venezuela) which have similar potential.

Step #5: The American deployment of IRBM’s in Turkey:

A missile defense system we are planning for Eastern Europe bears an ominous similarity to those Turkish missiles. While these new missiles are seen as defensive and a non-issue in America, the Russians see them as offensive and part of an American military encirclement. In October 2007, Putin warned, “Similar actions by the Soviet Union, when it put rockets in Cuba, precipitated the Cuban Missile Crisis.” [Putin 2007] Two months later Gorbachev questioned America’s stated goal of countering a possible Iranian missile threat, “What kind of Iran threat do you see? This is a system that is being created against Russia.” [Gorbachev 2007]

Step #6: Khrushchev’s deployment of the Cuban missiles:

While there is not yet a modern day analog of this step, serious warning tremors have occurred. In July 2008 Izvestia, a Russian newspaper often used for strategic governmental leaks, reported that if we proceed with our Eastern European missile defense deployment then nuclear-armed Russian bombers could be based on Cuba [Finn 2008]. During Senate confirmation hearings as Air Force Chief of Staff, General Norton Schwartz countered that “we should stand strong and indicate that is something that crosses a threshold, crosses a red line.” [Morgan 2008] While the Russian Foreign Ministry later dismissed Izvestia’s reports as false [Rodriguez 2008], there is a dangerous resemblance to events which led to the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The fact that we are not yet staring at the nuclear abyss is little cause for comfort. In terms of the sequence of events that turn a 99.9% safe maneuver into a fatal accident, we are already at a dangerous point in the process and, as in soaring, need to recognize complacency as our true enemy.

Section 4: How Risky Are Nuclear Weapons?

Even minor changes in our nuclear weapons posture have been rejected as too risky even though the baseline risk of our current strategy had never been estimated. Soon after recognizing this gaping hole in our knowledge, I did a preliminary risk analysis [Hellman 2008] which indicates that relying on nuclear weapons for our security is thousands of times more dangerous than having a nuclear power plant built next to your home.

Equivalently, imagine two nuclear power plants being built on each side of your home. That’s all we can fit next to you, so now imagine a ring of four plants built around the first two, then another larger ring around that, and another and another until there are thousands of nuclear reactors surrounding you. That is the level of risk that my preliminary analysis indicates each of us faces from a failure of nuclear deterrence.

While the analysis that led to that conclusion involves more math than is appropriate here, an intuitive approach conveys the main idea. In science and engineering, when trying to estimate quantities which are not well known, we often use “order of magnitude” estimates. We only estimate the quantity to the nearest power of ten, for example 100 or 1,000, without worrying about more precise values such as 200, which would be rounded to 100.

In this intuitive approach I first ask people whether they think the world could survive 1,000 years that were similar to 20 repetitions of the last 50 years. Do they think we could survive 20 Cuban Missile Crises plus all the other nuclear near misses we have experienced? When asked that question, most people do not believe we could survive 1,000 such years. I then ask if they think we can survive another 10 years of business as usual, and most say we probably can. There’s no guarantee, but we’ve made it through 50 years, so the odds are good that we can make it through 10 more. In the order of magnitude approach, we have now bounded the time horizon for a failure of nuclear deterrence as being greater than 10 years and less than 1,000. That leaves 100 years as the only power of ten in between. Most people thus estimate that we can survive on the order of 100 years, which implies a failure rate of roughly 1% per year.

On an annual basis, that makes relying on nuclear weapons a 99% safe maneuver. As with 99.9% safe maneuvers in soaring, that is not as safe as it sounds and is no cause for complacency. If we continue to rely on a strategy with a one percent failure rate per year, that adds up to about 10% in a decade and almost certain destruction within my grandchildren’s lifetimes. Because the estimate was only accurate to an order of magnitude, the actual risk could be as much as three times greater or smaller. But even ⅓% per year adds up to roughly a 25% fatality rate for a child born today, and 3% per year would, with high probability, consign that child to an early, nuclear death.

Given the catastrophic consequences of a failure of nuclear deterrence, the usual standards for industrial safety would require the time horizon for a failure to be well over a million years before the risk might be acceptable. Even a 100,000 year time horizon would entail as much risk as a skydiving jump every year, but with the whole world in the parachute harness. And a 100 year time horizon is equivalent to making three parachute jumps a day, every day, with the whole world at risk.

While my preliminary analysis and the above described intuitive approach provide significant evidence that business as usual entails far too much risk, in-depth risk analyses are needed to correct or confirm those indications. A statement endorsed by the following notable individuals:

- Prof. Kenneth Arrow, Stanford University, 1972 Nobel Laureate in Economics

- Mr. D. James Bidzos, Chairman of the Board and Interim CEO, VeriSign Inc.

- Dr. Richard Garwin, IBM Fellow Emeritus, former member President’s Science Advisory Committee and Defense Science Board

- Adm. Bobby R. Inman, USN (Ret.), University of Texas at Austin, former Director National Security Agency and Deputy Director CIA

- Prof. William Kays, former Dean of Engineering, Stanford University

- Prof. Donald Kennedy, President Emeritus of Stanford University, former head of FDA

- Prof. Martin Perl, Stanford University, 1995 Nobel Laureate in Physics

therefore “urgently petitions the international scientific community to undertake in-depth risk analyses of nuclear deterrence and, if the results so indicate, to raise an alarm alerting society to the unacceptable risk it faces as well as initiating a second phase effort to identify potential solutions.” [Hellman 2008]

This second phase effort will be aided by the initial studies because, in addition to estimating the risk of a failure of nuclear deterrence, they will identify the most likely trigger mechanisms, thereby allowing attention to be directed where it is most needed. For example, if as seems likely, a nuclear terrorist incident is found to be a likely trigger mechanism for a full-scale nuclear war, then much needed attention would be directed to averting that smaller, but still catastrophic event.

While definitive statements about the risk we face must await the results of the proposed in-depth studies, for ease of exposition the remainder of this article assumes the conclusion reached by my preliminary study – that the risk is far too great and urgently needs to be reduced.

Section 5: The Positive Possibility

In the mid 1970’s Whit Diffie, Ralph Merkle and I invented public key cryptography, a technology that now secures the Internet and has won the three of us many honors. Yet, when we first conceived the idea many experts told us that we could not succeed. Their skepticism was understandable because a public key flew in the face of the accumulated wisdom of hundreds of years of cryptographic knowledge: How could the key be public if its secrecy was all that kept an opponent from reading my mail? What was missed is that “the key” might become “two keys,” a public key for enciphering and a secret key for deciphering. Everyone could encipher messages using my public key, but only I could understand them by deciphering with my secret key.

Just as many cryptographic experts thought we couldn’t split the key and used arguments based on years of accumulated wisdom that were not applicable to the new possibility, most people have difficulty envisioning a world in which the nuclear threat is a relic of the past. While there is no guarantee that a similar breakthrough exists for ending the threat posed by nuclear weapons, this section provides evidence that our chances for survival are greater than we think.

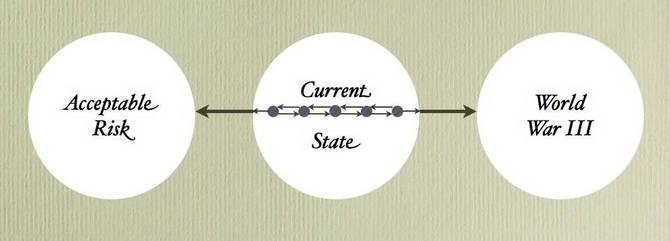

First Figure 3 must be modified by adding a third state in which the risk of nuclear catastrophe has been reduced thousands of times from its present level, so that it is at an acceptable level.

For the risk to truly be acceptable, this new state also must be a state of no return – its risk would not be acceptable if the world could transition back to our current state with its unacceptable risk. In this new figure, our current substate is near the middle of the current state of the world. We are not close to World War III, but neither are we close to an acceptable level of risk.

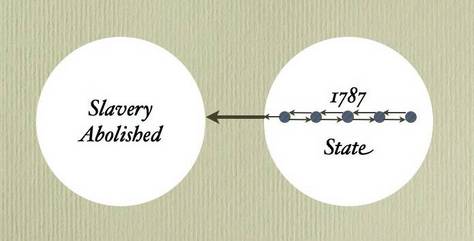

Much as people had difficulty envisioning public key cryptography before we developed a workable system, they also have difficulty envisioning a world that is far better than what they have experienced in the past. The evolution of the movement to abolish slavery in the United States provides a good illustration of that difficulty. In 1787 slavery was written into our Constitution. In 1835 a Boston mob attacked the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and dragged him half naked through the streets. In Illinois in 1837 a mob killed another abolitionist, Elijah Lovejoy. The next year, a Philadelphia mob burned the building where an antislavery convention was held [Goldsmith 1998, pages 11, 29]. In that environment or substate, few people could envision the end of slavery within thirty years, much less that citizens of Massachusetts, Illinois and Pennsylvania would give their lives to help bring about that noble goal.

While it was almost impossible to envision in 1787 – or even in the 1830’s – we now know that, as depicted in Figure 5 above, there was a sequence of substates that led to a new state in which slavery not only was abolished, but had no possibility of returning. The anti-abolitionist riots of the 1830’s – probably seen by most at that time as evidence of the insurmountable barriers to ending slavery – were actually a sign that a new substate had been reached and change was beginning to occur. There were no such riots in 1787 because the abolitionist movement was almost non-existent. By the 1830’s abolition was beginning to be seen as a serious threat to the supporters of slavery, resulting in the riots.

History shows that people have tremendous difficulty envisioning both negative and positive possibilities that are vastly different from their current experience. Therefore, even if I had a crystal ball and could predict the sequence of substates (steps) that will take us to the state of acceptable risk depicted in Figure 4, very few would believe me. As an example of the difficulty imagine the reaction if someone, prior to Gorbachev’s coming to power, had predicted that a leader of the Soviet Union would lift censorship, encourage free debate, and not use military force to prevent republics from seceding from the union. At best, such a seer would have been seen as extremely naive.

I had a milder version of that problem in September 1984 when I started a project designed to foster a meaningful dialog between the American and Soviet scientific communities in an attempt to defuse the threat of nuclear war, which was then in sharp focus. I was aware of the limitations that Soviet censorship imposed, but believed there still was some opportunity for information flow, primarily unidirectional. It had been eight years since my last trip to the Soviet Union and this visit was an eye-opening experience. While I did not know it at the time, I was meeting with people who were in the forefront of the nascent reform movement which would bring Gorbachev to power six months later, with some of them directly advising him.

Censorship was still the law of the land, so the scientists with whom I met could not agree with those of my views that contradicted the party line. But neither did they argue. I sensed something very different was brewing, but on returning to the U.S. I was often seen as extremely naive for believing that meaningful conversations were possible with persons of any standing within the Soviet system.

The steps leading to a truly safe world in Figure 4 would sound similarly naive to most people today. It is therefore counterproductive to lay out too explicit a road map to that goal. But how can one garner support without an explicit plan for reaching the goal? Until I realized the applicability of risk analysis, I didn’t see how that could be accomplished, but risk analysis provides an implicit, rather than an explicit map. No single step can reduce the risk a thousand-fold, so if the risk analysis approach can be embedded in society’s consciousness, then one step after another will have to be taken until a state with acceptable risk is reached. Later steps, which today would be rejected as impossible (which they probably currently are) need not be spelled out, but are latent, waiting to be discovered as part of that process.

The first critical step therefore is for society to recognize the risk inherent in nuclear deterrence. If you agree, please share this article – or whatever approach you favor – with others. Email is particularly effective since friends who agree can then relay your message to others. This article, a sample email, and other tools can be found on the resource page at NuclearRisk.org. “Just talking” might not seem to accomplish much, but as graphically depicted in Figure 4 and as noted by the ancient Chinese sage Lao Tzu, “The journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step.” If you have not already done so, I hope you will take the first step.

References

- [Blight & Welch 1989]: James G. Blight and David A. Welch, On the Brink: Americans and Soviets Reexamine the Cuban Missile Crisis, Hill and Wang, New York, 1989.

- [Burlatsky 1991]: Fedor Burlatsky, Khrushchev and the First Russian Spring, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1991.

- [Champion 2008]: Marc Champion, “U.N. Says Russian Jet Downed Georgian Drone”

, Wall Street Journal, May 27, 2008, page A16.

, Wall Street Journal, May 27, 2008, page A16. - [Finn 2008]: Peter Finn, “Russian Bombers Could Be Deployed to Cuba”

, Washington Post, July 22, 2008, Page A10.

, Washington Post, July 22, 2008, Page A10. - [Goldsmith 1998]: Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woddhull, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1998.

- [Gorbachev 2007]: “Gorbachev Worries About Missile Plan”

, Moscow News Weekly, November 29, 2007.

, Moscow News Weekly, November 29, 2007. - [Hellman 2008]: Martin E. Hellman, “Risk Analysis of Nuclear Deterrence”

, The Bent of Tau Beta Pi (the magazine of the American National Engineering Honor Society), Vol. 99, No. 2, pp. 14-22, Spring 2008.

, The Bent of Tau Beta Pi (the magazine of the American National Engineering Honor Society), Vol. 99, No. 2, pp. 14-22, Spring 2008. - [Morgan 2008]: David Morgan, “U.S. general warns against Russian bombers in Cuba”

, July 22, 2008 Reuters dispatch.

, July 22, 2008 Reuters dispatch. - [Putin 2007]: Vladimir Putin, “Press Statement and Answers to Questions following the 20th Russia-European Union Summit, Marfa, Portugal”

, October 26, 2007.

, October 26, 2007. - [Rodriguez 2008]: Alex Rodriguez, “Are Russians deploying a hoax?”

, Chicago Tribune, July 26, 2008.

, Chicago Tribune, July 26, 2008. - [Tatsis 2008]: Nicholas Tatsis, “A Brave New World: President Mikhail Gorbachev on the nuclear age and Russia’s future,” Harvard Political Review, January 13, 2008.

- [Wilson and Crouch 2001]: Richard Wilson and Edmund A. C. Crouch, Risk-Benefit Analsis, Harvard Press, Cambridge, MA, 2001.

- Glider photo courtesy of Bret Willat, Sky Sailing, Warner Springs, CA

This article was originally published at NuclearRisk.org

Martin Hellman is a co-inventor of public key cryptography, the technology that secures communication of credit card and other sensitive information over the Internet. He has worked for over twenty-five years to reduce the threat posed by nuclear weapons and his current project is described at NuclearRisk.org. He is a glider pilot with over 2,600 hours in the air.

Europe is heavily armed with nuclear weapons. Both Britain and France possess their own nuclear forces and the United States has a long history of keeping nuclear weapons on European soil. Britain’s nuclear force is estimated at under 200 weapons, with approximately 150 deployed on four Vanguard submarines and the remainder kept in reserve. France is thought to have approximately 350 nuclear weapons in its Force de frappe (strike force). The US keeps some 200-350 nuclear weapons in six countries: Belgium, Germany, Holland, Italy, Turkey and the UK. Recent unconfirmed reports indicate that the US has pulled its nuclear weapons out of the UK. If this is correct, approximately 240 US nuclear weapons remain in five European countries.

Europe is heavily armed with nuclear weapons. Both Britain and France possess their own nuclear forces and the United States has a long history of keeping nuclear weapons on European soil. Britain’s nuclear force is estimated at under 200 weapons, with approximately 150 deployed on four Vanguard submarines and the remainder kept in reserve. France is thought to have approximately 350 nuclear weapons in its Force de frappe (strike force). The US keeps some 200-350 nuclear weapons in six countries: Belgium, Germany, Holland, Italy, Turkey and the UK. Recent unconfirmed reports indicate that the US has pulled its nuclear weapons out of the UK. If this is correct, approximately 240 US nuclear weapons remain in five European countries.