This article was originally published by the Malta Independent.

Human beings are so adaptable that we have often accomplished what we previously thought ourselves incapable of achieving. The idea that men could fly was seen as absurd until the Wright brothers, Santos Dumont and others defied conventional wisdom. Because they had the courage to consider what everyone around them “knew” was impossible, today we fly higher and faster than any bird, and have even walked on the moon. Human slavery and the subjugation of women, once seen as immutable aspects of human nature, are now banned in every civilized nation.

Human beings are so adaptable that we have often accomplished what we previously thought ourselves incapable of achieving. The idea that men could fly was seen as absurd until the Wright brothers, Santos Dumont and others defied conventional wisdom. Because they had the courage to consider what everyone around them “knew” was impossible, today we fly higher and faster than any bird, and have even walked on the moon. Human slavery and the subjugation of women, once seen as immutable aspects of human nature, are now banned in every civilized nation.

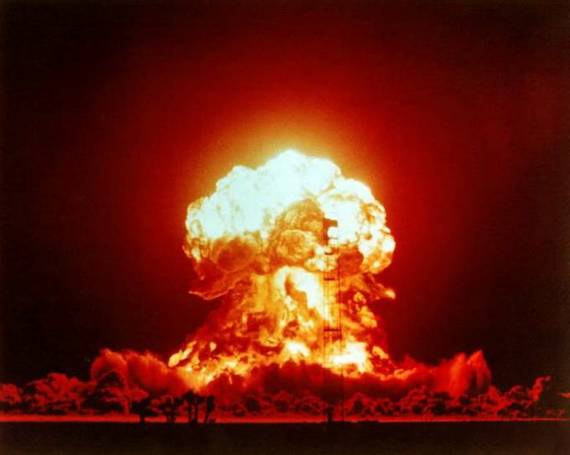

But one dream has eluded us: beating our swords into ploughshares, and learning to make war no more. In this instalment of this series of articles, I argue that we may be close to realising that age-old dream of Isaiah, and that nuclear weapons can be the catalyst for doing so, if only we will view them from the proper perspective.

The current environment might not seem conducive to that hope, with constant reports of wars, and threats of war. Yet a deeper look also shows signs of promise. Two books that appeared last year, Prof. Joshua Goldstein’s Winning the War on War, and Prof. Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature, both argued that the numbers paint a very different picture, with deaths due to war dropping from roughly 150,000 per year in the 1980s to 100,000 per year in the 1990s, and to 55,000 per year in the first decade of this century. While 55,000 deaths per year is a tragedy, that is far less than the number of deaths from road accidents!

In earlier writings, Prof. John Mueller argued that war was going out of style, much as duelling did in the 19th century: compare the millions of civilian deaths that were planned and actually celebrated during World War II, with the revulsion that even a few accidental ones produce today. Think of London, Coventry, Hamburg, Dresden, Nanking, Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki – or the siege of Malta – and compare them with the understandable outcry today when an attack on al Qaeda inadvertently kills a few women and children. There are also signs of hope on the nuclear front: the world’s arsenals have fallen several-fold, from a peak of over 70,000 weapons to roughly 20,000 today.

This data provides hope, but we should not become complacent about the threat posed by nuclear weapons – as Mueller, Goldstein, and to a lesser extent Pinker, tend to do. Part 3 in this series presented evidence that a child born today has at least a 10 per cent chance of being killed by nuclear weapons during his or her 80-year expected life – equivalent to playing Russian roulette with a 10-chambered revolver pointed at that child’s head. This level of risk may be lower than during the Cold War, but it is still unacceptably high. Now is not the time for complacency. Each generation is responsible for passing on a better world to their children. Now is the time to focus and help build the momentum towards eliminating this risk that could otherwise destroy the future.

A race is on between “the better angels of our nature” and the risk that a mistake, an accident, or simply a miscalculation, will bring on a final, nuclear war. By properly integrating the nuclear threat into the quest for world peace, we can motivate our better angels to run a bit faster, thereby increasing their chance of winning the race. To do that, we need to recognise that every small war – and even the mere threat of war – has some chance of escalating out of control, much as a terrorist act in Sarajevo was the spark that set off the First World War. The only real difference is that World War III would not have a successor.

The best-known example of a spark that nearly set off the nuclear powder keg is the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. Both superpowers were taken by surprise when a minor conflict suddenly erupted into a crisis that had them teetering on the brink of the nuclear abyss. Afterwards, President Kennedy estimated the chance of war as having been “somewhere between one out of three and even.” In Kennedy’s estimation, that crisis was equivalent to playing nuclear roulette – a version of Russian roulette in which the whole world is at stake – with a 2- or 3-chambered revolver.

Lesser crises have more chambers in the gun, but it doesn’t matter whether there are two chambers or two hundred. If we continually pull the trigger, it is only a matter of time before the gun goes off and civilization is destroyed. We have played this macabre game more often than is imagined. So long as we pretend that the potential gains from war outweigh the risks, each of our actions has some chance of triggering the final global war. Every “small” war – even those in Syria, or Libya, or Kashmir, or Georgia – pulls the trigger; each threat of the use of violence pulls the trigger; each day that goes by in which a missile or computer can fail pulls the trigger.

The only way to survive Russian roulette is to put down the gun and stop playing that insane game. The only way to survive nuclear roulette is to move beyond war in the same sense that the civilized world has moved beyond human sacrifice and slavery.

In the past, when it was merely moral and desirable, it might have been impossible to beat swords into ploughshares. Today, in our interdependent and interconnected global village, it is necessary for survival.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur recognised that reality in his 1961 address to the Philippines Congress: “You will say at once that, although the abolition of war has been the dream of man for centuries, every proposition to that end has been promptly discarded as impossible and fantastic. But that was before the science of the past decade made mass destruction a reality. The argument then was along spiritual and moral lines, and lost. But now the tremendous evolution of nuclear and other potentials of destruction has suddenly taken the problem away from its primary consideration as a moral and spiritual question and brought it abreast of scientific realism.”

There is potential for this to be the best of times, or the end of time, depending on which direction we take at this critical juncture. Technology has given a new, global meaning to the biblical injunction: “I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse; therefore choose life, that you and your descendants may live.”

Choosing life is not a passive decision, and requires an appropriate outward expression.

To remove this risk of extinction, we must shift from an old mode of thinking, which justifies war as being necessary for survival, to a new mode of thinking, which recognises war as the ultimate threat to our survival. When it was merely moral and desirable, it might have been impossible to beat swords into ploughshares, but today the lives of our children and grandchildren – and quite possibly our own – depend on our once again doing what we previously thought ourselves incapable of achieving. And, as outlined in earlier essays in this series, Malta is an ideal candidate for leading the way in an outward expression of this changed thinking, by becoming the first nation to treat the nuclear threat with the respect and attention it deserves. That would be a game changer, which would give our better angels a second wind in the race against oblivion.

Through supporting this series of articles, the ICT Gozo Malta project is seeking to create awareness that this is a global issue that can affect every one of us, including our children and their children. This is an issue that can be addressed in a meaningful way in a small country such as Malta. We in Malta have no desire to own or build weapons of mass destruction. We can leave a legacy for a safer world. Because of our small population and certain other advantages, it is easier for us to build a tipping point of public interest and for Malta to take a leadership stance, just as we already have in the area of nuclear power when Malta participated in the anti-nuclear Vienna Declaration, 25 May 2011. To begin this next process of change, and to ask our leaders to be more proactive in this cause, we require numbers! To make an outward expression, you can register your personal support on the online petition page, asking our government to make this issue a higher priority: www.change.org/petitions/global-nuclear-disarmament-malta.

If you would like us to keep you posted on new developments and ways you might participate in this effort to make Malta a beacon unto the nations of the world, please contact David Pace of the ICT Gozo Malta Project (dave.pace@ictgozomalta.eu).

The risk analysis approach I have advocated for reducing the threat of nuclear war doesn’t wait for a catastrophe to occur before taking remedial action since, clearly, that would be too late. Instead, it sees catastrophes as the final step in a chain of mistakes, and tries to stop the accident chain at the earliest possible stage. The news coming out of Ukraine for over a year has given us many options for doing that, but few in this country seem aware of the nuclear dimension to the risk. Russians are more aware, with a recent poll showing 17% who fear a nuclear war, versus 8% two years ago.

The risk analysis approach I have advocated for reducing the threat of nuclear war doesn’t wait for a catastrophe to occur before taking remedial action since, clearly, that would be too late. Instead, it sees catastrophes as the final step in a chain of mistakes, and tries to stop the accident chain at the earliest possible stage. The news coming out of Ukraine for over a year has given us many options for doing that, but few in this country seem aware of the nuclear dimension to the risk. Russians are more aware, with a recent poll showing 17% who fear a nuclear war, versus 8% two years ago.

The interim agreement to freeze Iran’s nuclear program has been praised by some as a diplomatic breakthrough and condemned by others as a prelude to nuclear disaster. A full appraisal must wait until we see what the follow-on agreements, if any, look like. In the meantime, here’s my take:

The interim agreement to freeze Iran’s nuclear program has been praised by some as a diplomatic breakthrough and condemned by others as a prelude to nuclear disaster. A full appraisal must wait until we see what the follow-on agreements, if any, look like. In the meantime, here’s my take: Human beings are so adaptable that we have often accomplished what we previously thought ourselves incapable of achieving. The idea that men could fly was seen as absurd until the Wright brothers, Santos Dumont and others defied conventional wisdom. Because they had the courage to consider what everyone around them “knew” was impossible, today we fly higher and faster than any bird, and have even walked on the moon. Human slavery and the subjugation of women, once seen as immutable aspects of human nature, are now banned in every civilized nation.

Human beings are so adaptable that we have often accomplished what we previously thought ourselves incapable of achieving. The idea that men could fly was seen as absurd until the Wright brothers, Santos Dumont and others defied conventional wisdom. Because they had the courage to consider what everyone around them “knew” was impossible, today we fly higher and faster than any bird, and have even walked on the moon. Human slavery and the subjugation of women, once seen as immutable aspects of human nature, are now banned in every civilized nation.